Standardising education kills creativity

I recently made some comments in the Educator Magazine about the risks of ‘standardising education’ and the resultant impact on so called ‘21st century’ skills. The debate on Twitter raged (as it so often does).

People argued, “Are listening, working collaboratively, communication skills or something else? Indeed, is creativity, or entrepreneurialism a skill that should be taught separately or is it caught through the delivery of content?”

Some may have thought: “Browning is speaking through his hat, where is the evidence to support his argument?”

Some Twitter users contend that the debate around 21st century skills is just a rehash of skills that were equally important in the 20th or even the 17th century. I agree with their arguments. Humans have always been, and have had to be, creative. Entrepreneurialism has been around since the invention of the wheel.

With the release of Gonksi2.0, some media commentators and educators would have us believe the recommendations are an assault on content and knowledge. The debate has been a polarising one and forces the question: Should we prioritise 21st century skills or a depth of discipline knowledge?”, as if you can’t have both.

I believe we can have both. Of course students need to be able to read, write and add up, and think creativity. They always have. The current imperative is the need to foster every student’s ability to think creatively or they will not be able to thrive in a world that has, and is being, transformed by technology.

I am all for evidence-based teaching practice, but the problem with the current evidence is that it has studied practices that are most effective in teaching students to read, write and add up along with their depth of subject knowledge.

In other words, the studies have all taken place in an outdated paradigm of school.

What schools need as well are studies of evidence-based practices that foster and grow every child’s ability to think creatively, to think like an entrepreneur. You measure what you value and you value what you measure; at the moment we don’t value these ‘skills’.

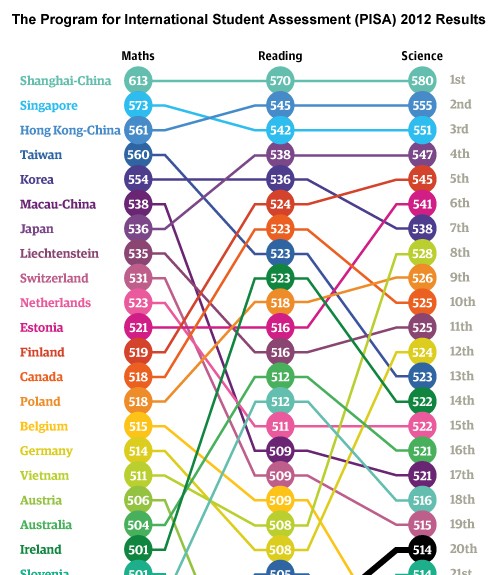

My concern is that if we don’t, countries like China will surpass us overnight. Fortune 500 companies there are injecting billions into research and development. They have realised what we are slow to grasp: the value of creativity and entrepreneurialism in a brave new world.

As politicians continue to seek a standardisation of education by imposing and publishing test results such as NAPLAN and Year 12 along with a rhetoric of ‘evidence-based’ practices that lift performance in these easily measurable areas, the more we will marginalise and ignore the ‘21st century’ skills.

The secret to fostering creativity lies in our approach to teaching. We have to stop trying to control the outcome.

For example, a simple strategy like holding up an example of work to give students direction of what a teacher (or parent) hopes they will produce at the end of the unit doesn’t give them guidance, instead it says, “if your work doesn’t look like this then you are wrong.”

Strategies like this teach students to comply and not to offer their thinking or perspective on a problem or piece of knowledge. How are such students meant to solve the problems and challenges facing the world if all they can do is re-hash what has already been tried? Perhaps that apocryphal quote attributed to Einstein is right: the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result

The same strategies are often reinforced at tertiary level where students learn that to get a good grade they have to write for their lecturer rather than offer an opposing, well-argued alternative view. Governments do the same with all the red tape imposed on new business ventures.

The reality of our world is that there are multiple perspectives on the same issues. There are multiple ways of arriving at an answer. There are multiple things still to discover. There is new knowledge to be created. If students learn that to be successful in education they must learn to comply, then creativity is left behind at 4-years of age.

Sir Ken Robinson said, “schools kill creativity”. I believe he is still right.

We have to address this. And now is more important than ever.